Two dreams about Europe and a mango lassi

Let’s take a look at Prague’s Indian restaurants where Bangladeshi employees work in condition hardly accetable for Europeans. Here they dream their dreams about the life in the West and here they wake up to the reality. Little do the costumers know about this as they get served their dishes. And little did I know until I got to teach them for the Czech language exam.

„Kdy jste se narodil? - When were you born?“ I ask Asif, the oldest of the three students. The topic today is dates. We have our lecture in a sunlit classroom of a language school. The rooms smells nicely – but it is the smell of the Indian restaurant where the three students work.

And the answer is somewhat surprising: „It says in my passport 14th of July 1985.“ This an awkward way to phrase it, but being a teacher I am accostumed to diverse life situations, so I just wink and react with understanding: „I see, you were born on the 14th of July, 1985, that’s a nice date.

„No, I was born 14th May, 1986.“

I look perplexed and the other two start laughing. „Things work differently in Bangladesh, it’s not like Europe.“

It leaves me with a feeling of parallel universes to realize that there are countries where the registry officers have a very imperfect information on the dates of birth of their citizens. Until then I thought our life experiences were more or less similar. The waiter, with whom you can only communicate in English, is here because being a waiter was his life’s dream. Surely he longed to work precisely here, in Prague, and he found his luck in this Indian restaurant. He is here anytime I come because this is a lovely place. He has that smile because he likes his work. And the music he keeps listening to again and again, these are his favourite songs.

Should I blame invisibility, or blindness for these assumptions?

Both.

Bangladeshis coming to the Czech Republic are not percieved as „immigrans“ in the negative sense. As holders of work or study visa they seldom provoke negative reactions. Superficially, they are not all that different from Indians, who we consider to be Hinduists. And while Bangladesh is largely a Muslim country, we do not really see it that way which is why the politically exploitable connection with Islam is absent. And as these people spend the majority of their time working, we seldom meet them. Which means, we know next to nothing about them.

Three phases of the Bangladeshi migration

Increasing numbers of foreign workers from Asia with short-term work visa is a trend all over Europe. According to Zbyněk Mucha from the Charles University who specializes in Indic studies and migration from Bangladesh, we can observe almost the same situation in our neighbour, Poland. Here too the presence of Indians, Nepalese, and Bangladeshis is increasing considerably. There are at the moment around fourteen hundred Bangladeshis in the Czech Republic and more are coming. The majority are men with short-term work visa.

According to Mucha, these Bangladeshis can be sorted into three phases depending on the time of their arrival. The first phase goes back to the seventies and eighties and resulted from the coopertation between the socialist Czechoslovakia and the similarly oriented Bangladesh. Students from various parts of Asia, Africa, and South America were coming to study at the local universities. In the case of Bangladesh, these were mostly young men with personal ties to the Bangladesh political elites. Many of these students stayed after they had finished their studies. They got married, found jobs, or started their own businesses. After Czechoslovakia split in 1993, a network of relations and market structures remained into which the second phase of migration was integrated.

The third wave starts in 2015, in which year the increased demand for foreign workers multiplied the number of Bangladeshis in the Czech Republic by ten.

While in the first and second phases there was a small and interconnected group of people, newly arrived Bangladeshis often do not have strategic contacts, they are alone and the only people they know are their new employers or a few classmates from college.

Dream about Europe

One of the representatives of the new generation is Asif. He studied microbiology in Dhaka at the urging of his father, who wanted his son to become a doctor. After graduating, he decided to try his luck in London, where his friend lived. He worked there for two years in a fast-food restaurant. His attempt to open his own business with his friend failed after a number of difficulties, including the non-renewal of his visa, and he had to leave the country. After returning to Bangladesh, he worked for two and a half years as an HR manager in a clothing factory for European and other markets. However, the work was time-consuming and poorly paid, so he decided to leave again, with an intention to study. That was in 2017.

"I went to an agency that helped students travel. New Zealand was an option because a relative was studying there. But they told me there was a possibility to go to the Czech Republic and that they issue visas quickly. I didn't know anything about the Czech Republic, but I thought - why not? The only thing I knew was that it had played for the football cup at some point. I came home and searched for the Czech Republic on the internet. From the YouTube videos with footage of Prague, I figured it was a beautiful country."

Asif's description of the choice of destination illustrates that deciding which Western country to head to is secondary. Mucha points out that a word that comes up a lot in the context of migration is „dream“. The dream of Europe, the idea of life in the West. The dream is not necessarily only an idealised idea of how life in Europe works, but also a partial achievement of European standards.

"The dream is actually to find that job, to be socially secure, to be able to afford at least the basics and know that you can support your family."

An entire segment of the economy in Bangladesh has formed around the dream business. One can speak of an established international "migration industry" based on the brokering of services for migrants. Financial remittances, i.e. money earned by Bangladeshis working abroad and sent back to Bangladesh, are also crucial for the Bangladeshi economy. Migration is considered a cultural constant here; virtually everyone knows a person who has left the country. Yet only a fraction of Bangladeshis go to Europe, since the most common destinations are the Middle Eastern countries. Asif himself saw his father, who worked in Saudi Arabia, for the first time at the age of six.

Welcome to Prague

Asif successfully passed the admission procedure to one of the Prague universities. The plan was to do his MBA there and then find a job.

"A friend, also a student from Bangladesh, was waiting for me at the airport. He escorted me to Strahov College. The accommodation cost 1,500 CZK a month (approx. 60 EUR). I had booked it myself online before.

I didn't have a smartphone, so my friend took me to Chodov, where they sold second-hand phones. The charges for calling were very high, ten minutes to Bangladesh cost 200 CZK (8 EUR). I had no data, I didn't know anything. Then I found out there was free wifi at the tram stops. I started going to different restaurants and looking for work. But everywhere they told me I had to speak Czech. I needed to work part-time to cover my expenses while I was studying."

He eventually found a job through a friend. "He gave me the address of a Bangladeshi who had lived here for twenty years and owned an Indian restaurant in Vinohrady. We agreed that I would work there for 52 CZK (2 EUR) an hour, with the proviso that I could come in when I wasn't studying."

But at the end of the month, Asif found that even though he was working enough, the earnings were small. He knew that to make a living, he had to make other arrangements. "A friend from Africa told me I could pack baggage at the airport. He said that if I packed two or three hundred suitcases a day, the earnings would still be good with tips. I earned 1,200 crowns in twelve hours, plus another 500 for tips, which was good.

School was about three days a week. When out of school, I worked. The shift started at 5 AM in the morning. I'd finish at 2 PM, eat, rest for a while, and work in the restaurant from 4 PM to 10 PM. I got home at eleven. Four days a week I slept three and a half hours a day. On the days I had school, I was insanely sleepy. I was in a bad place mentally, my brain wasn't working. I lost weight."

After several months in this regime, Asif met a Bangladeshi who had been in Prague for a long time, at the Vodičkova Street mosque. He suggested to Asif that rather than facing uncertain prospects of further st udies, he should provide financially for his family. Since the man owned an Indian restaurant, Asif called him after a few days of deliberation and told him that he would quit his studies and wanted to start working for him. As the lawyer Kostelecká points out, applying for a change of residence is a difficult process that often ends in rejection. But the stressful procedure worked out well for Asif.

Asif worked at the second restaurant for five years. "Compared to the first one, this restaurant was very nice. I was getting money every month. The remuneration was 12,000 (480 EUR) a month, while paying taxes and accommodation. As a waiter, I also earned almost 9,000 (360 EUR) a month in tips. I worked six days a week, eleven to twelve hours a day."

When the restaurant closed during the Covid, Asif found a job at a restaurant in the Old Town, where he still works today. "Most restaurants don't reimburse vacations. I was lucky, my employer pays my holidays. Owners often tell employees that if they take leave for a month and go to Bangladesh, they have to pay taxes or the owner will tell the ministry and the workers will be in trouble."

Asif is very happy with the third restaurant. "I work only four to five days a week. The earnings now are 26,000 including insurance and taxes. Plus tips, sometimes higher than the pay itself. A lot of tourists visit the place. I work from eleven to nine or from nine to ten. I set up the tables, the beer garden, make sure everything's in order. When the customers come in, I take the orders. If there's a problem, I call the owner, I don't have to worry about anything."

Asif is aware that he was abused by the first owner. "When someone new is here, the restaurant owners try to use it to their advantage. It's to their advantage because they know the newcomer is not familiar with how things should work."

Slave to the employee card

The problem of inequality between employers and foreign employees is also highlighted by Barbora Kostelecká, a lawyer who provides legal advice to clients of the human rights organisation Association for Integration and Migration. She speaks of an imbalance where on one side is a person with knowledge of the local system and on the other side is a foreigner who does not have access to the necessary information. And that, by definition, is a problem.

"For example, I often discover that working overtime is not paid properly. I've also seen employers pay wages net, but then ask the employee to repay the insurance fees they paid on their behalf. I also often have to explain to clients the concept of work leave - not just not working, but being paid while absent from work. Even mandatory breaks may not be clear to citizens of other countries."

What determines the lives of third-country nationals strongly is the fact that the possibility of staying in the country is directly linked to long-term residence. "The way foreigners deal with problems depends on the legal status of the person in our territory. When a person is under an employment card and their ability to stay here is tied to a particular employer, it tends to be very problematic." In other words, when a foreigner has problems with an employer, he or she often prefers not to let the matter be resolved, because the possible loss of employment also means the loss of the possibility to stay in the Czech Repiblic legally. Changing employers is often complicated for foreigners, and in the case of an employment card, virtually impossible in the first six months of residence. Since foreigners cannot afford to lose their residence after all they have invested financially and psychologically in migration, they often prefer to remain in the inconvenient situation.

Migration as a luxury good

"Sometimes I feel like an alien," Aman once told me when asked how he felt in Prague. Aman is twenty-nine. He likes to read, and you can hear it. When he finished his bachelor's degree in business in Bangladesh, he worked for a while at the daily news Svoboda. He has been working as a cook in Indian restaurants in the Czech Republic for six years.

He tells me about his beginnings. When he says that he was paid 16,000 CZK (650 EUR) for working twelve hours six days a week and the restaurant owner told him that he was paid the same or even worse elsewhere and threatened him that if he changed jobs he would lose his long-term residence, it makes me feel bad. But I was not ready for what comes next: „I gave the restaurant owner 10,000 euros for a visa. Most Bangladeshis do the same. He promised me that I would earn 3,000 euros, but the reality was 16,000 crowns. I paid the money up front. He claimed that the minimum salary in the country was over 2,500 euros and that I would earn even more if I worked well. When I arrived, I was totally shocked that everything was a lie.

I didn't get my money back. When my bosses at the restaurant yelled at me that I’m no good, I figured I was working for free anyway, because what I was getting I had prepaid myself. To this day, I still hate the guy. He was my family's neighbour in Bangladesh, I trusted him. He doesn't feel like he's doing anything wrong. I heard that another restaurant will be built with the money he got from me and two other workers this way." He did not tell his family, who paid for his trip to Europe, about what happened.

Migration is often mediated by the so-called 'dalals', known as dream sellers. These are informal intermediaries, very often distant relatives who live abroad, or recruiters in villages or smaller towns. These recruiters are also hired by employment agencies and are largely in a grey area outside the official structures. Although the Bangladeshi state has made some efforts to regulate migration, for example by enacting agencies as the only legal migration intermediaries, these rules are not enforced much in practice. And people who pay for travel arrangements often pay the price.

Awareness of what life in Europe is like varies widely. According to the indologist Zbyněk Mucha, however, it is not at all exceptional that people are relatively well informed and prepared for what awaits them. "There are many groups on social media where people share that things are not entirely rosy. On the other hand, there's a certain group of people, often just people with no contacts in the destination country, who will pay agencies and say: Get me there. That person has money and the family's endorsement and expects to get what is promised for his money. But there are a number of fraudulent agencies that profit precisely from the ignorance of new migrants. Young, relatively solvent men who are promised blue skies are then often targeted by recruiters. But when they arrive in Europe, they find that they have been deceived."

Mucha also points out that in order to understand Bangladeshi emigrants, we must keep in mind that migration to Europe is seen as a "luxury good" in Bangladesh. It is a product that many want to reach, but not all will succeed. It is then the difficulty for Bangladeshis to access the European labour market that is the reason for the high prices. If emigration succeeds, the specific form of success does not matter so much, even if it involves conditions unacceptable to Europeans. Migration to Europe is an end in itself. And the standards of what many people from Asia are willing to undergo for it differ from those of Europe. "In order to understand the perspective of particular people, it is also necessary to bear in mind that what we consider unacceptable is the reality of life for a large part of society in Bangladesh. Many new arrivals consciously choose years of hard work and life in this very difficult situation. They sacrifice for their families and for a better life, the vision of which is too distant in Bangladesh." The premise that the migrants here have it bad, then, tells us little about their perception of the situation.

Shared responsibility

According to Mucha, it is difficult to answer the question of who is responsible for stories like Aman's. "First of all, that the infrastructure for emigration in Bangladesh is very opaque and a number of actors are involved, including our embassy in New Delhi. This system pretends to be clearly set up, that the laws are working, but a number of individuals and groups of people are actively abusing it for their own benefit. When there are problems, it is easy to point fingers at specific individuals in the search for the culprits. Preferably at the dalal, who stands as if outside the system."

The aforementioned dependence of Bangladesh on remittances is also a major problem in this context. The system of issuing employee cards is quota-based, with only a limited number of cards issued per year for a particular region. Bangladesh falls under the Czech embassy in Delhi, which has an annual limit of one thousand one hundred cards. The fact that Bangladesh is competing with a significantly more populous India then leads to the fact that it has little incentive to advocate for workers' rights, as making trouble for the receiving state could put it at a competitive disadvantage.

We can also speak of significant problems on the part of the receiving countries in the case of Europe. They start with the way migrants are treated. "They are seen as cheap labour, and when we no longer need them, we send them back. It is about treating people as a product. States are not obliged to extend visas. The question is what happens to those people after the visa is not extended. Ideally, we imagine that people will leave when their visas expire, but of course that is not the case. Or we send them back, which is very expensive, so that is not going to happen either. And that's why it's easy to exploit foreign workers. The laws allow it, there's not much protection. The Czech Republic knows how the recruitment of workers is done, how non-transparent the system is, and how our activity and lack of interest is actually allowing it to continue to work this way. Of course, we are responsible to a large extent," says Mucha.

A family project

The disappointment and loss of trust that Aman experienced after arriving in Europe is still a sore subject for him. He lets his family believe that he is thriving and successful in Europe. "If they knew the truth, they would feel bad. My mother still cries every time we talk. I'm her youngest child, she would want to be with me. I'm scared. My mother is getting old and sick. She calls me every day. She doesn't really know what my job is. It makes me very sad. In our culture, parents sacrifice everything for us."

Not being able to share the trauma can lead to isolation from the family which already is thousands of miles away. Aman's words also illustrate the fact that Bangladeshis are not just emigrating for themselves. The goal of emigration is to improve the lives of the entire family, and it is often family members who sponsor the journey. Some people borrow money from their parents to pay them back during their first years in Europe, and often sell land and mortgage other assets. In other cases, people go into debt through usurious loans. In addition, debts can make it impossible to return to Bangladesh: when migrants find out that things are different from what they were told, they find themselves trapped because they have no chance of repaying their debts in Bangladesh.

"The reason why so many people are leaving Bangladesh is because of the huge unemployment. Many people see migration as the only way out. They can often only afford to go to Europe because their father or older brothers have gone to work somewhere in the Middle East. I often hear stories like 'before my father or older brother went to Bahrain, we had nothing, now we are fine. We bought more land, my younger brother is studying at university, we could send our child to study abroad...' People send home photos, which of course only show the beautiful things, and the bad things don't get to the relatives anymore," says Mucha.

When sobriety sets in, some resolve their situation by going underground and moving to another European country. It's a risky but time-tested way of operating. "Of course, you can't work legally in a new country, but it doesn't matter, because many people succeed, only a small number do not, and the benefits are huge. That's the general narrative and a fairly common practice."

Aman confirms that the consideration of trying one's luck in a country other than the one to which one has obtained a visa is present among migrants. "I had a friend who cried every day for two months straight. Everyone thought he would be successful in Europe. He told me that he starts work at five in the morning and comes back in the evening, that he doesn't earn enough. Then he threw away his papers in Portugal, taking advantage of the fact that at that time Portugal was offering legalisation to migrants who had entered the country illegally. Now he has a Portuguese passport. But if he goes to Bangladesh, he has to have a visa. When he was in Portugal, his mother died. He couldn't go back. It was an extremely difficult decision to make." Aman himself is clear on this point: "I never thought about this option. If I don't succeed here, I will go back to Bangladesh. I have a wife, a family, I have to have a chance to come back."

Passport with a hundred stamps

Aman worked at his first Indian restaurant for six months, then moved on. They paid 18,000 CZK (720 EUR), and the twelve hours a day, six days a week routine continued. After a year, he moved to a third Indian restaurant, where he still works as a cook. The working hours remained the same. In addition to 35,000 (1400 EUR) a month, his employer pays his accommodation. A variation on happy ending? Aman sees it differently: "I lost my freedom, I lost my dream. I didn't think I would be cooking in a restaurant. I didn't even know how to cook an egg. I had a dream that when I died, I would have a passport that said I had visited a hundred countries. And that there would be a room in my house with a library and in it at least three thousand books I had read.

Every night I think about falling asleep and then waking up and having to go to work. Sleep means work. When I wake up, I have to start getting ready for work. That's why I try to go to bed later, put it off. I feel like a student who doesn't want to go to school in the morning. It's like my parents are forcing me to go to school. The one who forces me is invisible, but forces me."

Such feelings are not unique. In addition to Aman and Asif, I have taught three other Bangladeshi restaurant workers. The course was from eight in the morning; they would not be available at any other time. They all looked exhausted all too often.

Earnings have improved, but working conditions are troubling Aman. When he scalded his feet and hands with hot water in a restaurant some time ago, his employer allowed him to see a doctor only after a fortnight. He said there was a shortage of workers and Aman's stay in hospital would put the business at a loss. Given the threat of losing his visa, Aman preferred not to protest. Working conditions? I am reminded of a sentence quoted by the Indologist Mucha during our conversation, "Working conditions is a fancy word." In other words, having the opportunity to discuss working conditions is itself a sign that you are not completely miserable.

One thing Bangladeshis agree on: when they come home from work in the evening, they usually have no energy for anything but scrolling through the internet. Aman recently got married and has no children yet, but Asif is worried about the effect work will have on his relationship with his eight-year-old daughter. He worries that he will miss his daughter's childhood and become distant from her, "My daughter has started first grade. She's in day care until four, and I get off work after nine. When my wife and I come home from work in the evening, our daughter is asleep and we don't really know what she did at home, only that she was on her tablet or phone. I don't have time to spend with her. She might ask me a question and I tell her to wait a minute, but then we both often forget about it. I'm exhausted, so is my wife. I can't take more than two days off in a row to go somewhere with my family because we are short-staffed. When I get permanent residence, I want to find another job, maybe in a supermarket or a café, one where you don't have to work evenings."

A future with permanent residence

A few months after our first conversation, Asif's dream of getting a more fulfilling job became closer to reality: he had gained permanent residency. I ask how he feels about the news. "I'm free now. Before, I wasn't because my permit was tied to a specific employer, so I had no choice. Sometimes I wanted to say something, but I preferred to keep quiet."

There are a number of benefits for third-country nationals in obtaining permanent residence, including free access to the labour market. The condition for obtaining it is that the foreigner has been living legally in the Czech Republic for five years (with the year spent studying counting as only half a year for the purposes of calculating the length of stay) and passes a Czech language exam. The required level was raised from A1 to A2 in 2021. As Asif himself points out, even the seemingly low level can pose a major challenge for foreigners.

"I know that if I had worked in a Czech environment, I would have been able to speak Czech well over the years. But with colleagues you usually speak Bengali, Hindi or English. People who have one day a week off at the weekend don't have a chance to learn the language. The school is closed and they barely have time to get their act together in that one day."

Asif doesn't think about the past and his shattered dreams in order to move on. He has a clear idea about his future: he doesn't want to be an employee. "Right now I want to work hard for a while, save some money and then open my own business. I would like to have a Bangladeshi restaurant, not an Indian restaurant, because everyone here already knows Indian cuisine. My wife might do a pastry course so that we can sell desserts as well. I'm not planning to go back to Bangladesh. I would be starting from scratch again."

Aman has a very similar plan. His priority is to pass the exam and obtain permanent residency. Right after that, he wants to get his wife to the Czech Republic. Aman describes the journey ahead of her as simple, probably compared to the extremity of her own migration experience, when she was completely abandoned to the fate of a first-generation migrant. „I only need to pay the lawyer here 23 000 CZK (950 EUR) to help her. She will have to go to India once or twice, because there is no Czech embassy in Bangladesh, then we will buy air tickets and that's it.

Aman's wife‘s future is not in the restaurants: she makes a living creating websites. Aman wants to open his own restaurant with a friend, but they haven't decided what kind of cuisine they will cook. Besides, he plans to import Bangladeshi textiles here. He would also prefer to live in the Czech Republic, if only because a Czech education means better prospects for his future family.

Currently, Aman lives with two colleagues in an apartment provided by the restaurant owner. When Aman's wife arrives, the landlord will give the couple another apartment. But Aman may not have to hurry too much: the process is likely to take several more months, given the length of the approval process.

Mango tree

"I feel like I'm throwing a rock at a mango tree, maybe I'll hit, maybe I won't," Aman summed up in our last lesson how he felt about the Czech exam, for which I, like other Bangladeshis, was preparing him. He says language is the one thing he doesn't like about the Czech Republic. Apart from the difficulty of the Czech language itself, he was also worried about the impossibility of focusing on his studies while working.

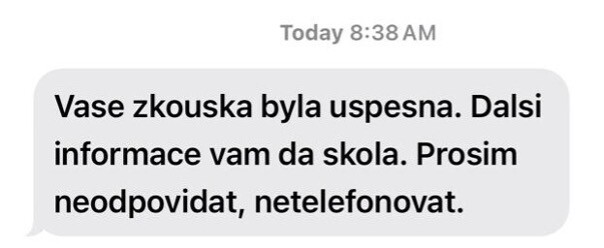

A few months later I am on the Mánes Bridge when I get a message from Aman. He had passed the exam on his first few attempts.

„Your exam was successful. Further information will be provided by your school. Please do not call or reply to this message.“

It's morning. I walk across the bridge towards the centre of Prague, where Aman is about to start slicing kilos of vegetables and Asif starts setting up tables for other customers a few streets away. The memory of a sentence uttered by Asif after he obtained permanent residency resurfaces in my mind:

"I'm not in jail anymore."

---

***

This article was published as part of PERSPECTIVES – the new label for independent, constructive and multi-perspective journalism. PERSPECTIVES is co-financed by the EU and implemented by a transnational editorial network from Central-Eastern Europe under the leadership of Goethe-Institut. Find out more about PERSPECTIVES: goethe.de/perspectives_eu.

Co-funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible.

![]()

![]()